Paths of Resistence – Case Studies Series

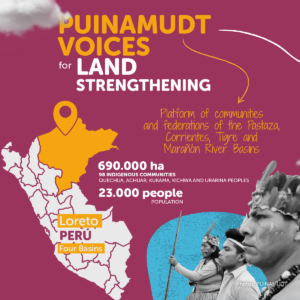

This case study shows how the federations (FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, ACODECOSPAT and OPIKAFPE) that represent the indigenous communities of the Four Basins of rivers Pastaza, Tigre, Corrientes and Marañón, in the Loreto region, north of the Peruvian Amazon, have pushed, in a unified manner through their PUINAMUDT Platform and in partnership with strategic allies, actions for organization, national and international advocacy, mobilizations and campaigns, and negotiation with the State, to defend their rights against the pollution and violations they have been experiencing due to oil exploitation in their territory since the 70’s, managing to get indigenous participation in initiatives for assessment of and solutions to the threats they face.

1. Case Study Video

2. The Case Study in a Nutshell

Basic Information

Indigenous Peoples: Quechua of Pastaza, Achuar of Corrientes, Kukama of Marañón, Kichwa of Tigre, and Urarina of Chambira river

Location: Loreto region, North of the Peruvian Amazon

Area: 694,695 hectares, approximately

Population: 98 indigenous communities, approximately

Main activities: Hunting, fishing, trade, family farming and community businesses

Local AEA partners involved: PUINAMUDT and Peru Equidad

Website: https://observatoriopetrolero.org/

3.1. Context and Challenges

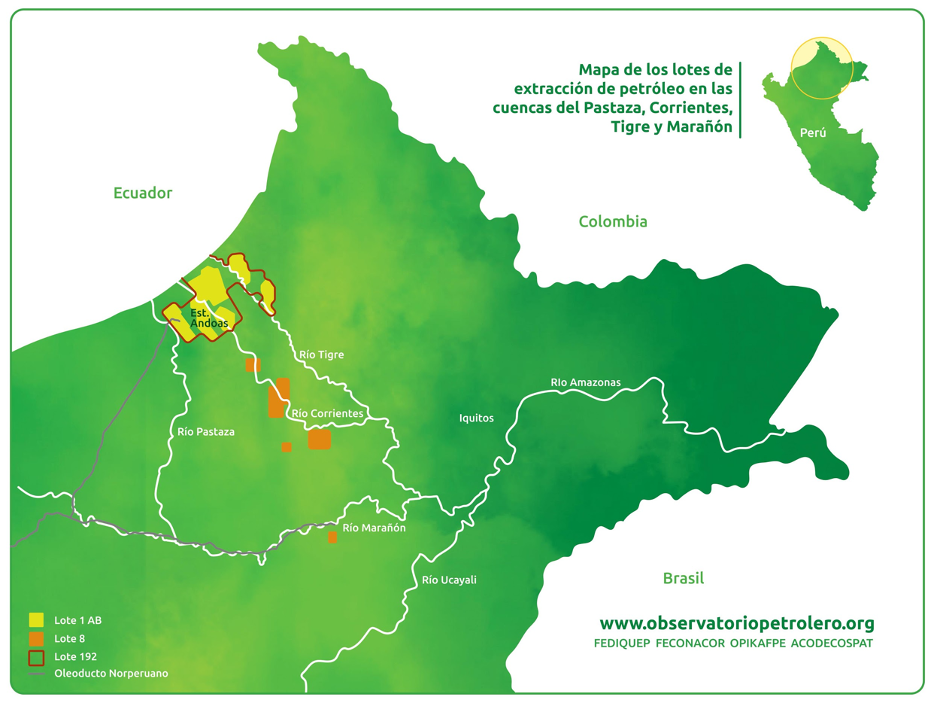

- The platform of the Amazonian Indigenous Peoples United in Defense of their Territories – PUINAMUDT (Pueblos Indígenas Amazónicos Unidos en Defensa de sus Territorios) is made up of four federations that together represent a total of 98 indigenous communities in the Loreto region, located in the north of the Peruvian Amazon, in an area of approximately 694,695 hectares. These communities belong to the indigenous peoples Quechua from river Pastaza, Achuar from river Corrientes, Kukama from river Marañón, Kichwa from river Tigre, and Urarina from river Chambira. They live between the four basins of rivers Pastaza, Tigre, Corrientes and Marañón.

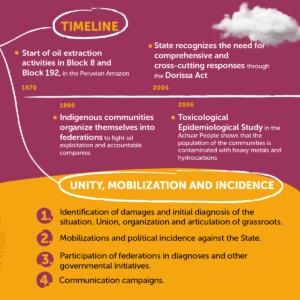

- For 50 years, these communities have endured violations of fundamental rights, including harm to their health and contamination of their food and water sources as a result of oil extraction activities in their territories: at sites referred to as Block 8 and Block 192 (former Block 1AB), which overlap the ancestral territories of these indigenous communities.

- With reference to Block 8, the national company Petroperú operated Block 8 between 1971 and 1996, and then, Argentine company Pluspetrol Norte S.A., a subsidiary of Pluspetrol Resources based in the Netherlands, operated the same block from 1996 to the present, under a concession agreement. This year of 2021, before the end of its concession contract, Pluspetrol announced its liquidation as a company. On the other hand, Block 192 was operated by U.S. company Occidental Petroleum Company (OXY) between 1971 and 2000, and then by Pluspetrol Norte from 2001 to 2015 under concession agreements. From 2015 to February 2012, Canadian company Frontera Energy operated Block 192 under the terms of a service agreement.

“We are not poor, but we have been made poor, our territory has been stolen from us”

Alfonso López, president of the ACODECOSPAT, cocama Indigenous organization

- Block 192 accounts for the largest oil production area in Peru, with an average daily production of 10,000 barrels of oil per day (17% of Peru’s oil production). The Block’s production is generally marketed in international tenders, being sold to the highest bidder in the international market, with sales registered mainly to La Pampilla Refinery (Peru), Chile, the United States and South Korea, according to Perupetro. On the other hand, Block 8 is one of the largest oil reserves in the country. Both blocks are the oldest in the Peruvian jungle.

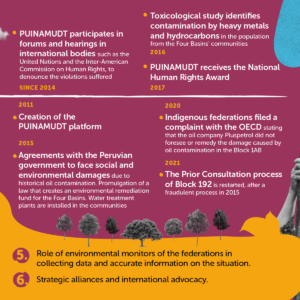

Location of Blocks 8 and 192 in the Four Basins

- The 98 communities affected by operations in Blocks 8 and 192 and by NorPeruvian Oil Pipeline (ONP – Oleoducto NorPeruano) are represented by four federations: Quechua Indigenous Federation from Pastaza (FEDIQUEP); Native Communities Federation from the Corrientes Basin (FECONACOR); Cocama Association for the Development and Conservation of San Pablo de Tipishca (ACODECOSPAT); and Organization of the Amazonian Kichwa Indigenous People of the Peru-Ecuador Border (OPIKAFPE). Since 2011, these federations work together through the PUNAMUDT platform. In 2017, the four federations received the National Human Rights Award in Peru, in recognition of years of struggle protecting the rights of indigenous nationalities affected by nearly half a century of oil exploitation.

- In the region, the main forms of pollution derived from oil extraction activities have been: discharge of highly toxic contaminated production waters (with high concentrations of heavy metals, toxic salts and hydrocarbons) into the main water sources and rivers of the territories; constant oil spills, poor remediation practices (such as burning or land removel at polluted sites) as well as company dumps. This has been occurring for decades due to the lack of environmental supervision, insufficient protection of rights, lack of maintenance or change of infrastructure of the operations that cross indigenous territories (which generates spills), and absence of effective environmental compensation and remediation measures. This is added by the weak, insufficient and fragmented regulatory framework in Peru, which does not ensure environmental protection or guarantee rights against the impacts of extractive companies.

- With reference to the negotiation process with the government to obtain a response to the violations of rights of the Achuar people, the first formal commitment between the State, the operating company (at the time Pluspetrol, for the two blocks) and the communities was reached in 2006 upon execution of the Dorissa Agreement. Among other measures, the agreement set forth that Pluspetrol should deliver $40 million soles over 10 years to improve the population’s health in the area of oil extraction, while the regional government should deliver 11 million soles for several development projects. The commitments were not fully complied with. In the Dorissa Agreement, the Achuar people made a commitment to start and implement their own Independent Indigenous Environmental Surveillance program, an initiative that was also launched in other basins.

- In 2015, after several years of indigenous demands and mobilization, the Peruvian State carried out a prior consultation process for the concession of Block 192 for the next 40 years. The process concluded in violation of the peoples’ right to prior consultation, as the Ministry of Energy and Mining imposed a single agenda item, closing off the possibility of dialogue on other social and environmental security and rights issues: Accept only 0.75% of the resources coming from oil production to finance a Social Fund that would be destined to community projects. As most of the communities did not agree with such condition, imposition and abuse, the Ministry of Energy and Mining unexpectedly decided to end the process and seal its agreement with a minority of communities Following these events, after 15 days of indigenous mobilization and suspension of oil production, the State reached agreements with the communities to ensure better conditions to address the problems in their territories.

- After a lengthy struggle (involving community mobilizations in 2017, 2018 and 2019) summarized in this Case Study, a new Prior Consultation process is guaranteed for the next concession agreement for Block 192. This new process was resumed in 2019 with a new Prior Consultation Plan; however, said process was unilaterally interrupted by the Ministry of Energy and Mining. By the end of 2020, based on the demands presented jointly by the federations that comprise PUINAMUDT, an addendum to the Consultation Plan was made, including the participation of other governmental sectors (such as health; housing, construction and sanitation; and transportation and communications), to provide answers baed on an integral perspective in a Prior Consultation process to be resumed in 2021. In addition, it is worth mentioning that, for the new process, there are formal commitments by the State with the communities, such as that of the Vice-Minister of Hydrocarbons, Victor Murillo Huamán, who said that no progress will be made in the new operations of Block 192 until a Prior Consultation satisfactory to all parties involved is completed. However, after the outbreak of the so-called “second wave” of COVID-19 in Peru, the process was again halted.

The emblematic case of Lake Shanshococha, in the Pastaza River region, illustrates the socio-environmental irresponsibility of the PlusPetrol company and the magnitude of the damage caused. In 2012, indigenous organizations informed the Peruvian authorities that the lake was completely covered in oil. In an attempt to mitigate its responsibility for the spill, upon learning that a Commission of the Peruvian Congress was going to promote a field visit to verify the complaint, the PlusPetrol company drained the lake, making it disappear. This action was taken without prior notice to the Peruvian government. This case is emblematic because it demonstrates the frequent practice of the company, repeatedly denounced by indigenous organizations, of trying to hide leaks and contamination of its authorship.

- Although the operation of Block 192 was paralyzed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, oil spills continued to take place, as it is believed that the company did not carry out adequate maintenance of the facilities: there were 14 oil spills between March 2020 and January 2021.

- On December 16, 2020, Pluspetrol Norte publicly announced its winding up, and thereby its withdrawal from Block 8, under the allegation that the Environmental Assessment and Oversight Agency (OEFA) requires it to remedy environmental liabilities left by the company that operated in the same area prior to Pluspetrol Norte’s arrival. On December 30, 2020, the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Energy and Mining and the OEFA stated that, with respect to the Peruvian legal framework, Pluspetrol Norte S.A. must assume the rights and obligations of the transferor due to the position taken by Pluspetrol in the concession agreements for the operation of Blocks 8 and 192, in which Pluspetrol had assumed the obligation to comply with the binding provisions. To date, the OEFA has established that Pluspetrol Norte is responsible for more than 1,500 impacts identified in the area of these Blocks and, for failing to comply with the respective remediation, the OEFA has imposed more than 4,000 UITs (Mandatory Tax Units) of compulsory fines (equivalent to over US$4.8 million), in addition to respective sanctions. Pluspetrol would abandon Block 8 with a series of pending commitments with the indigenous communities in the area.

3.2. Strategies: key-factors to overcome the challenges

- Union, organization and concerted advocacy structure: The federations representing the indigenous communities of the Four Basins region were created in the 90’s aiming to carry out mobilizations demanding solutions to the violations of their rights and the environmental pollution affecting their territories and respective effects on the communities’ health. Despite belonging to different indigenous peoples and river basins, these communities and their federations, affected by the same impacts and the same players (oil companies and the Peruvian State), decided to unite in a single Platform to develop a common agenda and coordinate joint strategies and actions, thus creating the PUINAMUDT platform in 2011.

“The government is willing to dialogue, but we don’t know their minds, their hearts, what they are thinking for they have just recently listened to us”

Aurelio Chino, president of the Quechua from Pastaza Indigenous Federation (FEDIQUEP)

- Identification of limitations and initial assessment of the situation: Being located in a border region without a strong institutional presence of the State, the claims and demands of the communities and organizations were initially directed only to the company in charge of the extractive activities, for those damages that were more evident. Nevertheless, given the company’s inertia, the worsening of conflicts and recognition of the problem magnitude, the communities and their federations realized the need for promoting actions of political influence aimed at the State, in addition to the demands aimed at Pluspetrol. At the beginning of the dialogue process with the Peruvian State, PUINAMUDT representatives found that, among other things, the State did not have complete, detailed, organized, comprehensive information on the actual situation in the territories, mostly because (i) their main source of information on the environmental situation was the oil companies themselves, and (ii) supervisions by the sector authorities were very favorable to the companies. In addition to the technical limitations, the State was also subject to the company’s high power of influence. In such a scenario of scarce information, lack of transparency and failure to record the great magnitude of the impacts ‘in situ’, the federations managed to pressure the State to open, in 2012, a space for multisector dialogue, in order to obtain comprehensive answers and actions in the face of the situation. Just as some of the leaders pointed out, the communities would teach the State how to do its job.

- Mobilizations and negotiation with the State: After multiple and persistent protests, in 2012, in the wake of Alianza Topal community’s peaceful mobilization, in the presence of the Health Minister and the Environment Minister, the President of the Loreto’s Regional Government, the Public Defender’s Office (Defensoría del Pueblo), and the apus (leaders) of the communities, a Multisector Commission was created and made official and is still in operation today. The Commission has served to establish a dialogue and coordinate the agenda between different sectors. This space has also served to offer a comprehensive perspective of the responses and problems faced by the communities, recognizing them as social and environmental issues and engaging high level authorities of different fronts of the public sector. An important outcome of this institutional dialogue process between the State and the federations is the Lima Agreement, executed on March 10, 2015, which provides for the drafting of several assessments, studies and plans carried out by the State’s technical bodies. However, more than five years after execution of the agreement, its implementation has reached 35%, according to PUINAMUDT’s indigenous federations. Still, the Agreement has allowed for important milestones and advances in the process:

- Emergency and Health Emergency Declarations (published between 2013 and 2014).

- Toxicological and Epidemiological Study “Levels and Risk Factors of Exposure to Heavy Metals and Hydrocarbons for the Inhabitants of the Communities of the Pastaza, Tigre, Corrientes and Marañón River Basins of the Department of Loreto” 2016-2018 (published in 2019)

- Analysis of the Health Situation of the Amazonian Indigenous Peoples living in the region of the Four Basins and the Chambira River (published in 2020)

- Comprehensive and Intercultural Health Care Model for the Pastaza, Corrientes, Tigre, Marañón and Chambira River Basins in the Loreto region 2017-2021 approved by Ministerial Resolution 594-2017- MINSA (Health Ministry)

- Installation of Water Treatment Plants in 65 communities in the four basins, as well as 65 Intradomiciliary Water and Sanitation projects in 80 communities, which are currently being implemented.

- Titling agreements for 100 indigenous communities, still partially fulfilled with approximately 30 communities that received their land titles.

- Environmental Remediation Contingency Fund for the Four Basins, which has indigenous participation through a Board of Directors and so far amounts to more than 200 million soles (about 48 million dollars). Through this fund, environmental remediation processes with participation of the indigenous federations will start in 2021 in Block 1AB (now Block 192), under the Peruvian State’s responsibility.

- Furthermore, State commitments were formally entered into through agreements that represent responses and actions to specific problems, recognizing the violation of social rights, especially in environmental, health and other areas. Likewise, in response to the demand for active participation in the processes of planning, follow-up, surveillance of the commitments undertaken, and supervision of the resources that would be used in actions as a result of the violations. Other milestones achieved are of a regulatory nature, given that the State’s experience with PUINAMUDT made it possible to improve some of the soil Environmental Quality Standards (EQS) at the national level, as well as to have an impact on the creation of laws, such as the Environmental Remediation Contingency Fund (Law no. 30,321), among others.

“We are in this fight first to teach the company, because if you don’t tell them what has wronged you, they do whatever they want. And the State is also going to learn that it gave permission to an irresponsible company, and that we are not going to allow it anymore”

Julio Maynas, apu (leader) of the Achuar native community of Nueva Jerusalén

- Role of the federations’ environmental monitors in data compilation and accurate information about the situation: Since 2006, faced with the inertia of the companies and the State in providing information on contamination levels, the communities’ territorial monitors in the area of Blocks 8 and 1AB have been the main parties responsible for collecting data, providing information and making environmental complaints regarding oil leakage and contamination in the oil areas, in a work comprising surveillance and control of the indigenous territory from an comprehensive perspective. The indigenous monitors, based on their in-depth territorial knowledge, and with the support of expert international institutions that train and supervise them, carry out their work equipped with GPS, smartphones and drones to film, photograph and locate polluted sites. The information gathered by the indigenous monitors is sent to their corresponding federations, which, jointly through PUINAMUDT, warn national authorities and urge competent bodies to take suitable remedial action. It is worth stressing that in recent years the participation of women in monitoring the territories has expanded, in addition to their increased role as communal authorities (as apus and lieutenants) and, above all, as spokespersons for the federations comprising PUINAMUDT. Data collected in monitoring actions are an important basis not only for supporting advocacy campaigns, but also for promoting investigations by government authorities. For instance, thanks to the work of ACODECOSPAT’s environmental monitors in the Marañón basin, an environmental judge was able to visit Block 8, in the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, to conduct an environmental inspection that resulted in a fine of 29 million soles for Pluspetrol in 2013. Monitors from the independent indigenous environmental monitoring programs have been able to report up to 1,209 sites and 51 water bodies polluted in Block 1AB (now Block 192). A study carried out by the Regional Health Department of Loreto (2009) found hydrocarbons present in the waters of the Corrientes Basin at rates 10 times higher than those allowed worldwide. The work and contribution of indigenous environmental monitors is recognized by institutions such as the Environmental Assessment and Oversight Agency (OEFA), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), among others. In 2018, the indigenous environmental monitoring programs of FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR and OPIKAFPE received the prize “Conectarse para Crecer” awarded by Fundación Telefónica.

- Participation of the federations in governmental assessments, both at the environmental and health impact levels: In 2016, a Toxicological and Epidemiological Study was conducted, where blood, urine and food samples were collected, in addition to environmental samples of soil and water. This study was developed by specialists of the Ministry of Health and counted on the participation of the Four Basins’ federations from the beginning until the delivery of the final report. Furthermore, each village had an interpreter, who was appointed and supported by the federations. As a result, it was found that the population located within 50 km of the oil activity was the one that exceeded by far the maximum reference values of heavy metals allowed in national and international regulations. It was also found that children under the age of 12 were the most affected population; for example, 47.8% of this population had arsenic levels in urine above national reference values. In Corrientes, a child under the age of 12 had six times the national regulation maximum arsenic reference value. In Pastaza, a child under the age of 12 reported 4 times the national reference value for lead in blood in children under 12 years of age (10ug Pb/dL in blood; although, internationally, the reference limit is 5ug Pb/dL in blood). In fact, in the region of Block 192 alone, 2,722 barrels of oil were spilled in the brief period between 2009 and 2011. Based on a report by the National Human Rights Coordinator and Oxfam, 1,209 sites have been impacted by oil activity in the two Blocks. Thirty-two of these areas contain enough polluted material to fill 231 soccer stadiums. Between 2000 and 2009, there were 189 oil spills in Block 192 and 155 spills in Block 8. Also in the area of health, in December 2020, at the request of the indigenous federations as part of the commitments undertook by the State, the Ministry of Health published report Analysis of the Health Situation in the Pastaza, Corrientes, Tigre, Marañón and Chambira Basins, a two-year research project carried out in the communities’ territories. On the other hand, thanks to the struggle and demands of the indigenous federations, the Peruvian environmental authorities conducted the first thorough environmental assessments with indigenous participation in Blocks 1AB and 8, between 2012 and 2013, after more than 40 years of oil activity. These evaluations were the foundation for consecutive statements of environmental and sanitary emergency in the Four Basins.

- Communication campaigns: One of the strategies adopted by the PUINAMUDT platform to reverse actions infringe their rights has been communication campaigns to publicize their demands. In this context, the platform has been efficient in launching focused campaigns with specific demands, with the company or the Peruvian State as target audience, but also in promoting wider campaigns that seek to raise awareness of its cause among the general population. The campaigns are planned in two stages: (i) information; publicity; content and advocacy (with graphic, digital and radio mobilization components); and (ii) mobilization communication (territorial actions), which are developed in an integrated manner in theme-based structures for specific strategies of the Prior Consultation process, including peaceful mobilizations with strong community presence and other demonstrations, even in Lima. As an example, in 2018, campaign ‘Pluspetrol, clean NOW!’ (¡Pluspetrol, limpia YA!) aimed at obtaining environmental remediation of damages caused by PlusPetrol as a result of oil exploration activities in Block 192. In response to the fraudulent Prior Consultation process in 2015, for the 40-year concession contract for Block 192, the organizations comprising PUINAMUDT promoted, in 2019, campaign ‘Prior Consultation #WithoutTraps’ (Consulta Previa #SinTrampas) targeting the Peruvian State. The campaign demanded effective participation of the Four Basins’ communities in the Prior Consultation process, based on the Consultation Plan prepared by the platform – requiring that the consultation process take place in the territory and not in Lima or Iquitos, where the community could not participate – while presenting proposals to be included as requisites for the concession of the Block for extraction. The campaign included radio programs that were broadcast in the communities, as well as informational leaflets about their demands. Finally, PUINAMUDT promotes campaign ‘#HealthyAmazon’ (#AmazoníaSana), which seeks to inform about the damage caused by the high concentrations of heavy metals in water, fish and soil. The campaign displays metal banners that, with the slogan “Metal doesn’t hurt, heavy metals do” (El Metal no daña; los metales pesados, sí), help to inform a wider public of the violations experienced by the communities of the Four Basins, gaining the solidarity of different audiences.

- Strategic alliances: During the PUINAMUDT development process, the platform joined other institutions that, with their technical support, contribute to the struggle, complaints and negotiations headed by the federations. The consolidated alliances that fit into this aspect are the Center for Public Policies and Human Rights, Perú Equidad, the National Human Rights Coordinator (CNDDHH), Oxfam Peru, the Amazon Center of Anthropology and Practical Application (CAAAP), the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) and E-Tech International, which, among other contributions, offer technical support for monitoring violations, drawing up reports, and for the complaints formalized by the platform. A partnership with Digital Democracy, within the scope of the All Eyes on the Amazon Program, has ensured the promotion of workshops (2019) to environmental monitors on the use of the MAPEO application (Desktop and Mobile) to collect data on pollution in the territory.

- Furthermore, PUINAMUDT is a member of the Peruvian Amazonian indigenous national organization called Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Forest (AIDESEP – Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana), which also includes regional organizations such as the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the East (ORPIO) and the Regional Coordinator of Indigenous Peoples of San Lorenzo (CORPI-SL), in the Loreto region of the northern Peruvian Amazon. It is also a member of the National Platform of People Affected by Metals, Metalloids and Other Chemical Substances (Plataforma Nacional de Personas Afectadas por Metales, Metaloides y Otras Sustancias Químicas). In addition, as a public authority, PUINAMUDT maintains communication, coordination and follow-up with the Public Defender’s Office on issues related to the entire agenda of dialogue with the State. Other relevant institutions have also participated in the PUINAMUDT process, which have been involved at different levels due to their level of expertise, transparency and renowned institutional profile, such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), among others.

- International advocacy: Inactivity or insufficient remediation at the national level prompts the platform to look for international support, so that international mechanisms, relying on regulations and agreements to which Peru is a party, can put pressure on governments and companies responsible for social and environmental damage. In April 2017, PUINAMUDT counted on the support of Perú Equidad to file a complaint with the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) at its 61th session. The complaint sought to get an answer from Netherlands in relation to the actions of Pluspetrol Resources, headquartered in Amsterdam, in the region of Blocs 8 and 192. The complaint based its appeal on the Maastricht Principles (2011) which, among other measures, establish that States must take the necessary measures to ensure that companies with their headquarters in their country do not infringe economic, social and cultural rights in third countries. In 2019, the indigenous federations of the PUINAMUDT platform, with technical and legal support from CNDDHH, CAAAP, Perú Equidad and Oxfam, denounced the health and environmental crisis in their communities before a public hearing at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In addition, in March 2020, the federations of the Four Basins submitted a complaint to the Dutch government’s contact at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The complaint alleges that Pluspetrol breached several of OCDE guidelines and that the company did not foresee or remedy the damage caused by oil contamination in Block 192, which impacted local water and food sources, as well as the health and welfare of about 25,000 people. Lastly, according to the document, the company has established a highly complex corporate structure through tax havens that would allow it to bypass tax control and conceal the corporate entities and owners. The complaint to the OECD was signed by FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, OPIKAFPE and ACODECOSPAT, as well as civil society institutions from Peru and the Netherlands, such as Perú Equidad, the Center for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), Oxfam Novib and Oxfam in Peru, among others. In March 2021, the complaint was officially accepted by OECD.

3.3. Benefits: added value and case impacts

- Unity of the federations over time: The consolidation of the PUINAMUDT platform as a space for consensus and unification of the communities it represents was one of the main results obtained in these 10 years of organization, struggle and initiatives for demands and dialogue with the State. This milestone is particularly important given the diversity of cultures made up of almost a hundred communities of different nationalities in a vast territorial area, which manages to remain united and strong in order to safeguard their rights and the conservation of the healthy forest. Within this ambit, the platform provides a consolidated representation hand in hand with the communities, with a relationship of trust, since the agenda proposed by PUINAMUDT reflects, in fact, the demands of the communities of the Four Basins.

- Governance and indigenous participation: Although there are still many challenges for the full fulfillment of their rights and due reparation from companies such as Pluspetrol, Petroperu, Frontera Energy and others for the damages caused, the mobilization of the communities and the processes of dialogue with the Peruvian State, conducted by PUINAMUDT in the last decade, have ensured the presence and participation of indigenous peoples in mechanisms and the State agenda, through their own innovative proposals on the measures to be taken by the State for justice and reparation in strict observance of indigenous rights. Indigenous participation in this process was achieved through territorial mobilization, specific advocacy, and continuous dialogue with PUINAMUDT, lawsuit after lawsuit against the State, which, despite recognizing the historical debt with these peoples, and even apologizing to the communities for the damage inflicted, does not demonstrate a real, deep and sustained change in this historical relationship based on the infringement of rights and periodical conflicts. In this regard, despite the agreements being affected when governments and managers change, PUINAMUDT was successful in proposing and sustaining the agenda, maintaining pressure and continuity of the processes, with key achievements such as the recognition of the right to a new Prior Consultation process for the concession of Block 192, in spite of the State’s initial refusal to carry it out. This gain is not restricted to PUINAMUDT and extends to other indigenous communities and organizations, because, to a certain extent, it sets a precedent for the participation of indigenous representatives in political processes that reflect their rights, and although this right is recognized by treaties such as the ILO Convention 169, to which Peru is a signatory, it is not always observed in practice. Above all, besides the benefits for Peru’s indigenous populations, the State itself benefits, once the advocacy and political negotiation fostered by PUINAMUDT has taught the State mechanisms for the design of public policies that have generated achievements even to date; for example, new environmental quality standards (2014), Law 30,321 (2015) or the Model of Integral Intercultural Health Care (2017), which designed as a response to the critical situation encountered by the communities due to oil pollution, has served as one of the models for the development of the Indigenous Covid-19 Plan drawn up by the Peruvian State in 2020.

- Strengthening of the role of environmental monitors: The role of environmental monitors emerged in response to the lack of adequate inspection and assessment of the damage caused by hydrocarbon pollution. Over the last fifteen years, the territorial monitoring teams have multiplied throughout the river basin territories and have even gained recognition by government agencies, playing a key role in territorial and environmental surveillance. Their work independence contributes to the communities always being informed about what is happening in the territories and, because the monitors are members of the communities, the data they collect is trusted by the communities, which is not the case with data provided by the companies or the State. However, it is still necessary to improve mechanisms for the overall protection of the monitors’ actions, in addition to measures for broader recognition to support their work.

4. Timeline

Learn more about:

Videos

- Puinamudt Loreto YouTube Channel

- 2015: Message to the Peruvian state: “My territory is my life” (Oxfam) [Mensaje al Estado peruano: “Mi territorio es mi vida”]

- 2016: What is the Kukama Territorial Surveillance? ACODECOSPAT tells you (PUINAMUDT) [¿Qué es la Vigilancia Territorial Kukama? ACODECOSPAT te lo cuenta (PUINAMUDT)]

- 2018: ¡Pluspetrol, clean Now! (PUINAMUDT) [¡Pluspetrol, limpia ya!]

- 2018: New oil spill in Block 192 affects the Achuar Nuevo Nazareth and Nuevo Jerusalén communities (PUINAMUDT) [Nuevo derrame de petróleo en Lote 192 afecta as comunidades Achuar Nuevo Nazareth e Nuevo Jerusalén]

- 2019: Elmer Hualinga: the indigenous monitor who uses technology to monitor oil spills (Mongabay) [Elmer Hualinga: el monitor indígena que usa la tecnología para vigilar derrames de petróleo]

Files

- 2006: Dorissa Agreement [Acta de Dorissa]

- 2013: Declaration of Environmental Emergency in the Pastaza River Basin: Ministerial Resolution no. 139-2013-MINAM [Declaración en Emergencia Ambiental en la Cuenca Pastaza: Resolución Ministerial Nº 139-2013-MINAM)]

- 2013: Declaration of Environmental Emergency in the Corrientes River Basin: Ministerial Resolution no. 263-2013-MINAM Declaración en Emergencia Ambiental en la Cuenca Corrientes: Resolución Ministerial N° 263-2013-MINAM]

- 2013: Declaration of Environmental Emergency in the Tigre River Basin: Ministerial Resolution no. 370-2013-MINAM [Declaración en Emergencia Ambiental en la Cuenca Tigre: Resolución Ministerial N° 370-2013-MINAM]

- 2014: Declaration of Environmental Emergency in the Marañón River Basin: Ministerial Resolution no. 136-2014-MINAM [Declaración en Emergencia Ambiental en la Cuenca Marañón: Resolución Ministerial Nº 136-2014-MINAM]

- 2015: Lima Agreement of March 10, 2015, signed between the Presidents of the Federations of the Pastaza, Tigre, Corrientes and Marañón River Basins and the Representatives of the National and Regional Governments of Loreto. [Acta de Lima].

- 2016: Toxicological and Epidemiological Report for Four Basins (Peru Health Ministry- MINSA) [Informe Toxicológico Epidemiológico para Cuatro Cuencas]

- 2017: Report submitted by the Center for Public Policy and Human Rights (EQUIDAD), Amazonian Indigenous Peoples United in Defense of their Territories (PUINAMUDT), the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (GI-ESCR) and FIAN to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on at the time of considering the Sixth Periodic Report of the Netherlands during the 61st period of Committee’s sessions. [Informe].